In Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma she revisits the work of artists after we’ve learned about the terribleness of them personally. “How do we separate the maker from the made? …And how does our answer change from situation to situation? Are we consistent in the ways we apply the punishment, or rigor, of the withdrawal of our audience-ship? …And is it simply a matter of pragmatism? Do we withhold our support if the person is alive and therefore might benefit financially from our consumption of their work? …I asked myself more and more often: what ought we to do about great art made by bad men?”

In a mix of critical assessment and sometimes personal appreciation for their influential works, Dederer’s chapters on focus on individuals Polanski, Woody Allen, Michael Jackson, Picasso, Carl Andre, etc. and later in the book, investigates the myth of the “masculine genius” while considering problematic women like J.K. Rowling, Virginia Woolf, and Willa Cather, questioning whether “products of their time” meant “we’re better now.” But are we?

“It was June of 2017. Trump had been in office for months. People were unsettled and unhappy, and by people I mean women, and by women I mean me. The women met on streets and looked at one another and shook their heads and walked away wordlessly. The women had had it. The women went on a giant fed-up march..”

I appreciated the ways in which Dederer’s personal questions brought the reader deeper into the murky harder consideration: “what do we do about monstrous people we love?”

Dederer includes the protests in remembrance of Ana Mendieta as an example of intervention: “Starting as early as 1992, a group known as the Women’s Action Coalition began a series of protests and interventions under the title ‘Where is Ana Mendieta?’ Meaning, where is she in the institution, in the museum? The question form of the title reinforced the idea of Mendieta’s silence; the voice that had gone unheard. As the years went by and the actions continued, new protestors joined in, many of them surprisingly young… By showing up and raising their voices about the life of a woman who’d died before they were born, their protest said something simple: Things hadn’t gotten better. Not really… These protestors were really saying we were no better than we were on the day Ana Mendieta fell to her death.”

Connecting the first two book recommendations was also a theme of recovery. Both Dederer and Tendler provided an unsparing, non-sentimentalized review of their own experiences. In Monsters, Dederer shares, “There are two kinds of people who stop drinking: those who simply don’t care for the stuff, and those who care for it too much. I was the latter kind. And when a person like me quits drinking, they are confessing, on some level, that they have become an unmanageable monster. Am I a monster? The answer turned out, was a resounding yes… Recovery, as a way of living, makes you see things from the monster’s point of view. You see things from his point of view because you are him. You sit in the rooms and listen and you hear terrible, terrible things, but they are ordinary things. Because everyone in that room has gone through them.”

I read Anna Marie Tendler’s Men Have Called Her Crazy in a single weekend – I found Tendler’s unsparing examinations of her own struggles to be so compelling, both specific to her own history but also common with other women in recovery – the men in her life and the impact of those relationships both trauma and addiction.

“Women displaying anger – even acknowledging anger – are deemed pathological. As a woman I know this and have acted accordingly. I have hidden my anger, buried it, for fear of being judged or persecuted – only to have it explode out of me later, after being pushed and pushed past my limits. What occurs then is a cyclical pattern of obfuscation and explosion, instead of steady acknowledgment, distress tolerance, and conflict resolution. Anger becomes a quality of shame rather than a workable emotion, one that can spark creativity, realizations, and transformation. Men have analyzed my anger, often forgetting or refusing to understand that part of what makes me so angry is having to contort through social dynamics and notes that they have created. Men have judged me and men have called me crazy, trusting their own neutrality… The anger I feel sometimes towards men is not usually as personal as it might seem. Some of the anger has to do with them, but I also know some of it is the product of a life experience coalesced long before I had romantic relationships… I believe men have the ability to look outside themselves, to question how their actions affect the women around them, and to exist with more awareness to others’ experiences, should they want to do that. I have been lucky to know a few men who do.”

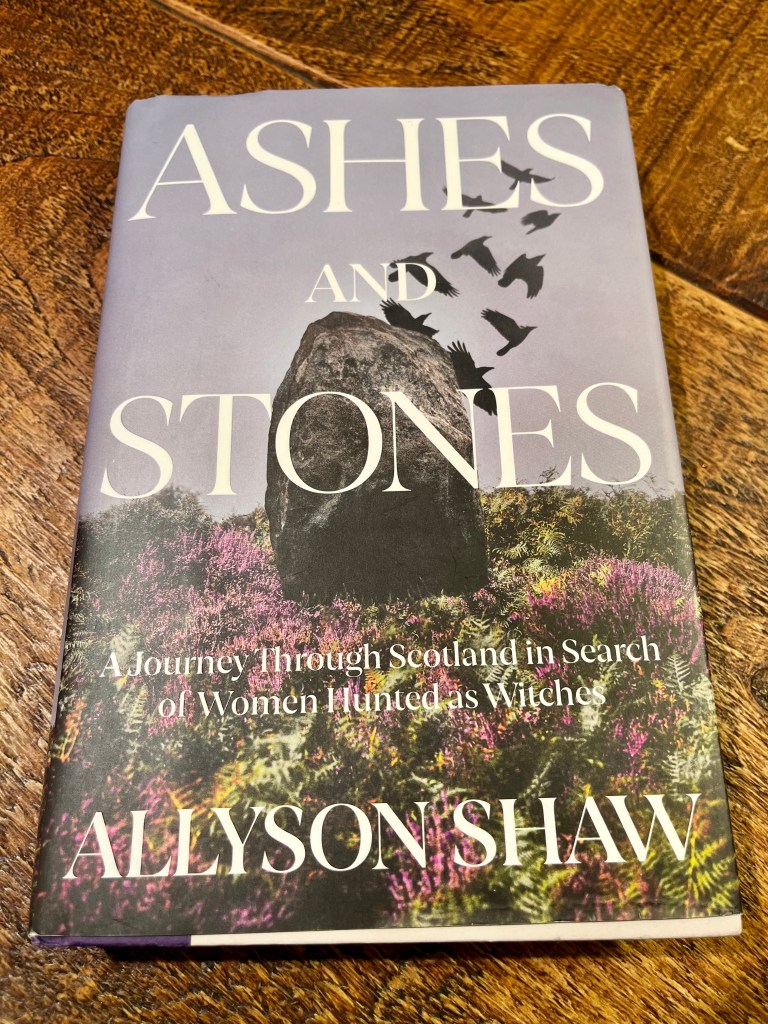

Those of you familiar with my ongoing multi-years Burning Times Project, begun in 2006, that continues with research and handmade poppets in remembrance of those killed as witches in the Witch Trial Era, will not be surprised that I found such deep connection and resonance with the beautiful, haunting journey across the sites of Scotland that Allyson Shaw writes about with such reverence in Ashes and Stone: A Journey Through Scotland in Search of Women Hunted as Witches: “The history of the witch-hunts subsumed me – it was older than the place I’d come from, the place I’d once called home. I’d been taken in, but what or who had received me? The voices of the accused became more than a historical record. It was as if they spoke directly to me – to us. Even if it would take hundreds of years, someone would hear them… I travel to places of execution; I write to them. I take the measure of the archives and read between the lines of the kirk sessions’ scribes. Every morning, I tap away, making words stand in for physical space, for a true memorial to the atrocity. New cases and monuments come to light as I write, and no doubt this will continue after the writing is complete… True memorial is more than the legal gesture of a pardon, apology or designated heritage location. It is emotional, intellectual and spiritual work… History isn’t just a distant mirror – it’s a fractured one. For women and non-binary people, the shards are particularly ill-fitting and sharp. Many pieces are missing or deliberately destroyed. The impulse to wholeness is human. We invent and fill in the blanks, courting ghosts and making do in our reparations… The stones, hills, mazes and menhirs I’ve gathered in this book form another map of the dead.”